Printed from acutecaretesting.org

June 2021

Point-of-care testing in the Emergency Department - Getting to the point

Introduction

Emergency department (ED) medicine is a specialty that faces unique medical and organizational challenges. Emergency department staff must treat a wide variety of acute injuries and illnesses in a rapid and expedient manner to ensure optimal patient care. This makes logistical organization arguably more important for EDs than for other hospital departments, especially since EDs are susceptible to overcrowding through a number of causes, including an aging population and increasing referrals from primary care [1].

Maintaining ED patient turnover and mitigating overcrowding relies on timely triage, diagnosis, and initiation of proper treatment. While factors such as capacity and standard operating protocols (SOPs) impact ED efficiency, the availability of accurate data drives the smooth operation of an effective ED. Point-of-care testing (POCT) has proven to be essential to the timely acquisition of diagnostic data, which facilitates faster decision making and improves patient care [2].

POCT and ED diagnostics

Physicians rely on accurate and timely information to make clinically relevant decisions [2]. In the ED, personnel gather most of this information via diagnostic monitoring, testing, and assaying. Reducing the turnaround time—the time it takes to gather diagnostic information and supply it to the clinician—is important in health care as a whole, but it is especially paramount in the ED, where a decision-making delay of minutes could make a dramatic difference for patients suffering serious acute illnesses or injuries [1,2,3].

There are several ways to evaluate whether POCT improves ED diagnostic workflows and accelerates physician decision-making. One way is to look at the performance and turnaround time for the diagnostic tests themselves, another way could be to measure patient length of stay (LOS) but focus should also be on improving workflow procedures among health Care professionals in the ED.

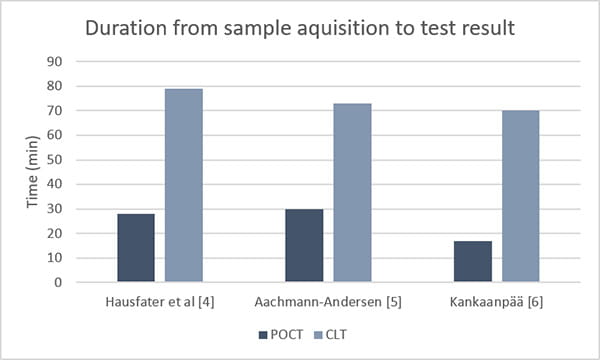

In a randomized controlled trial performed in a French hospital involving more than 20,000 patients in an emergency department, Hausfater et al. [4] found that POCT had a significant impact on time elapsed between sample registration by central laboratory or POCT technician and result display in the server (TTR). The following analytes were measured by POCT on whole blood: complete blood count (CBC), electrolytes, urea, creatinine, calcium, blood gas, and lactate, liver enzymes, bilirubin, lipase, and creatine kinase, and immunoassays such as troponin T, NT-proBNP, C-reactive protein, procalcitonin, human chorionic gonadotropin, D-dimer. The mean TTR reduction was 51 minutes in the POCT arm, with a mean TTR of 28 and 79 minutes in the POCT and control arms, respectively. Unfortunately, the improved TTR did not reduce patient LOS in the ED significantly, which may be explained by TTR not being the only bottleneck contributing to LOS and overcrowding [4].

This data is supported by other similar studies. Aachmann-Andersen et al. [5] performed a single center study in a Danish hospital. Comparing two periods of ED patients who required blood testing to determine patient priority and degree of urgency, such as blood gas, leucocytes, D-dimer, and CRP they found that the response time for central laboratory analyses was longer than for POCT throughout the period by as much as 49 minutes on average. Aachmann-Andersen et al. concludes that POCT seems to have led to a higher capacity for patient turnover, with more patients discharged directly from the emergency department, fewer re-hospitalizations, improved efficiency, and faster results for important lab tests. However, the study also indicates that in order to benefit fully from POCT other contributors to overcrowding have to be controlled [5].

A study performed in a Finnish hospital ED for ambulatory patients in an emergency department [6] showed a similar trend. Here, LOS was reduced significantly, mainly by an introduction of a comprehensive POCT panel including complete blood count, sodium, potassium, glucose, C-reactive protein, creatinine, alkaline phosphatase, alanine aminotransferase, bilirubin, amylase, and D-dimer. The improvements were achieved over two phases enrolling in total 4,798 patients and comparing, among others, time from blood sampling to results ready, with a control phase (n=1559) prior to the introduction of POCT.

Figure 1. Introducing point-of-care testing (POCT), dramatically reduces time from sample acquisition to test result compared to when clinical laboratory testing (CLT) is used alone.

It can be difficult to evaluate POCT effectiveness by looking at LOS. However, a study by Lewandrowski [7] showed a decline in mean ED LOS from 8.46 to 7.14 hours for patients who underwent D-dimer testing to exclude venous thromboembolism (VTE). The D-dimer POCT was the main contributor to the reduction in ED LOS with a turnaround time (from blood draw to result) of 25 minutes vs ~2 hours.

Studies like these are supported by observational studies from clinical staff. In an observational study conducted in a New York State academic ED, 56% of treating physicians believed that having POCT results available at the time of initial evaluation improved care by either shifting the focus of their evaluation or contributing to earlier treatment/disposition [8]. These sentiments were echoed by both ED care team members and patients enrolled into the aforementioned study conducted by Hausfater et a. [6]. A satisfaction survey showed that patients were significantly more satisfied during the POCT period than in the central lab period regarding overall care in the ED, waiting time, and delay in obtaining results (p<0.001). Also, the staff members from ED and the laboratory responded favorably to POCT in the ED (94 %), while 92% estimated that POCT had sped up ED patient care and 90% would be in favor of implementing POCT routinely in the ED [4].

POCT and ED logistics

Diagnostic testing is just one part of ED care, and it is important that the gains offered by POCT implementation translate to improvements within the workflow procedures in the ED. If care is not taken, it is possible for faster POCT results to create new bottlenecks. In particular, access block—where patients are cleared by physicians to leave the ED but cannot because insufficient space is available in in-patient wards—is a concern [9]. Another important factor is accessibility and ease-of-use. POCT systems must not offer a sharp learning curve for hospital staff and must readily integrate within existing hospital practices for data collection, dissemination, and storage [10]. That said, properly integrated POCT has been proven to streamline patient flow and alleviate ED overcrowding with minimum disturbances to existing practices [6].

Routines and SOPs are important for many occupations, but perhaps doubly so for emergency departments where time is often at a premium. It is important that POCT devices integrate well with existing SOPs to limit the amount of re-education required. For example, devices should provide enough technical capacity and flexibility to accommodate specific information needs that a hospital may have. Some may need devices that transmit results to remote locations through wired or wireless networking in alignment with existing data communication protocols, while others may prefer to record test results manually [10].

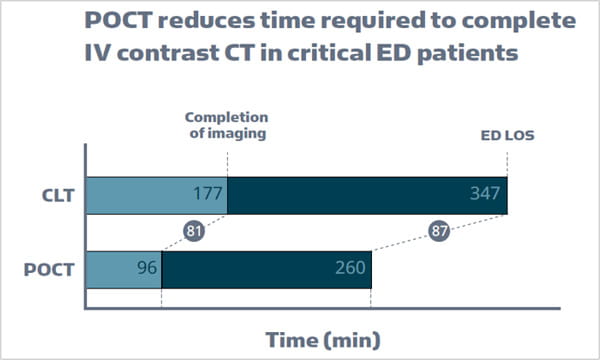

The best POCT devices only require minor adjustments to existing ED practices for integration, while also enabling larger workflow alterations. Studies have shown that POCT incorporation can translate to shorter wait times prior to physician consultation, assessment, and treatment. In a study published by Singer et al. in the American Journal of Emergency Medicine, found that introducing comprehensive bedside POCT of a basic metabolic panel with hemoglobin, hematocrit, troponin I, lactate, BNP, and INR for critically ill or injured ED patients reduced the time elapsed from triage to the completion of a IV contrast CT scan by almost 50%, a time- savings of 81 minutes [8].

In a major Finnish hospital, POCT not only reduced testing turnaround times but also helped the hospital implement an early assessment team (EAT)-based triage model. According to Kankaanpää et al. [11] the EAT triage model helped the ED team make better use of POCT, resulting in shorter patient stays compared to POCT alone or EAT coupled with central laboratory testing. Importantly, from a staffing and personnel perspective, these changes necessitated rearranging work shifts, but required no additional resources.

Beyond workflows and organization, practitioner proficiency represents the other major logistical obstacle to POCT implementation. To that end, POCT instrumentation is designed with ease-of-use and accessibility in mind [12]. Studies that show beneficial effects of POCT implementation typically also report high levels of satisfaction among physicians and nurses. Singer et al. [13] documented that ~90% of surveyed physicians at a New York State hospital reported that POCT testing was easy to request, with a similar proportion of nurses noting that POCT was easy to use.

POCT and ED patient care

When seeking to improve either ED diagnostics or logistics, the goal is the same: improved patient care.

Patient care quality can be analyzed in many ways, but in general, the targeted endpoint for ED patients is to move them out of the ED. This can entail initiating and completing urgent treatment and stabilizing their conditions sufficiently to move to a non-emergency ward, diagnosing non-immediately life-threatening conditions and triaging to in-patient care, or discharging patients with mild or minor afflictions. As such, many studies that evaluate patient care quality use “length-of-stay (LOS)”— the time from ED arrival to ED departure—as their primary metric. However, there are also many studies that prefer to use “disposition determination,” the time taken from ED arrival to when a physician order is given concerning either discharge or admission to a hospital floor, feeling that this metric is more valid because it is wholly under the control of the ED [8].

Like the aforementioned studies which reported considerable reductions in TTR and LOS [4, 7] Kankaanpää et al. [6] saw an 82 (~19%) minute decrease in overall ED LOS while Singer et al. [13] noted that an 81 minute decrease in time-to-imaging became an 87 minute (~25%) decrease in overall ED LOS. A subsequent prospective case- controlled trial conducted by Singer et al. likewise reported a significant decrease (0.9 hours, ~10%) in the time from ED admission to disposition, as well as a considerably larger (albeit not statistically significant) empirical decrease in mean ED LOS duration (2.9 hours, ~23%) [8].

Additionally, moving patients out of the ED in a timely manner has secondary effects. Having fewer patients at any given time in the ED eases overcrowding, allows staff to pay more attention to each patient, and translates into generally happier patients. Singer et al. reported that a majority of both physicians (62%) and nurses (71%) surveyed said that they felt POCT improved patient satisfaction [13].

Figure 2. Introducing point-of-care testing (POCT) dramatically reduces the time necessary to complete IV contrast CT in critical emergency department (ED) patients. A decrease of 81 minutes was noted compared to when only clinical laboratory testing (CLT) was used. This translated into an 87 minute decrease in overall AD length of stay (ED LOS). Data is sourced from A.J. Singer et al., J Emerg Med, 2018.

POCT is worth the effort

POCT has the potential to improve ED quality of care [13], but its implementation must fit with the specific needs of the individual institution. POCT is not a “one size fits all” solution to ED problems. POCT use, alone or in tandem with other adaptations like early assessment teams or workflow optimization, can contribute to dramatic improvements in testing turnaround times, overall ED logistics, and most importantly, quality of patient care.

Implementing POCT means incorporating it within existing ED diagnostic and logistic workflows, thereby minimizing disruptions for healthcare practitioners. That said, POCT instrumentation is flexible enough to accommodate a wide variety of situations and scenarios common to EDs.

References+ View more

- St John A, Price CP. Benefits of point-of-care testing in the emergency department. Acutecaretesting.org March 2018. Accessed May 2021.

- Wilke P. How to optimize patient flow and outcome in ED - The impact of point of care. Acutecaretesting.org June 2013. Accessed May 2021.

- Regan B, O’Kennedy R, Collins D. Advances in point-of-care testing for cardiovascular diseases. Advances in Clinical Chemistry 2020.

- Hausfater P, Hajage D, Bulsei J et al. Impact of Point-of-care Testing on Length of Stay of Patients in the Emergency Department: A Cluster-randomized Controlled Study. Academic Emergency Medicine 2020.

- Aachmann-Andersen NJ, Bjerrum PJ, Rasmussen SW, Schmidt TA. POCT is a true asset in the emergency Department. Scandinavian Journal of Trauma, Resuscitation and Emergency Medicine 2012 20(Suppl 2):P38.

- M. Kankaanpää et al. Comparison of the use of comprehensive point-of-care test panel to conventional laboratory process in emergency department. BMC Emerg Med 2018; 18, 43.

- Lee-Lewandrowski E, Nichols J, Van Cott E et al. Implementation of a Rapid Whole Blood D-Dimer Test in the Emergency Department of an Urban Academic Medical Center: Impact on ED Length of Stay and Ancillary Test Utilization. American Journal of Clinical Pathology 2009; 132, 3.

- Singer AJ et al. Early point-of-care testing at triage reduces care time in stable adult emergency department patients, J Emerg Med 2018; 55,2.

- Chaisirin W et al. Role of point-of-care testing in reducing time to treatment decision-making in urgency patients: A randomized controlled trial. West J Emerg Med 2020; 21, 2.

- Pines JM et al. Integrating point-of-care testing into a community emergency department: A mixed-methods evaluation. Acad Emerg Med 2018; 25, 10.

- M. Kankaanpää et al. Use of point-of-care testing and early assessment model reduces length of stay for ambulatory patients in an emergency department. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2016; 24, 1.

- St. John A, Price CP. Existing and emerging technologies for point-of-care testing. Clin Biochem Rev 2014; 35, 3.

- Singer AJ et al. Comprehensive bedside point of care testing in critical ED patients: a before and after study. Am J Emerg Med 2015; 33, 6.

References

- St John A, Price CP. Benefits of point-of-care testing in the emergency department. Acutecaretesting.org March 2018. Accessed May 2021.

- Wilke P. How to optimize patient flow and outcome in ED - The impact of point of care. Acutecaretesting.org June 2013. Accessed May 2021.

- Regan B, O’Kennedy R, Collins D. Advances in point-of-care testing for cardiovascular diseases. Advances in Clinical Chemistry 2020.

- Hausfater P, Hajage D, Bulsei J et al. Impact of Point-of-care Testing on Length of Stay of Patients in the Emergency Department: A Cluster-randomized Controlled Study. Academic Emergency Medicine 2020.

- Aachmann-Andersen NJ, Bjerrum PJ, Rasmussen SW, Schmidt TA. POCT is a true asset in the emergency Department. Scandinavian Journal of Trauma, Resuscitation and Emergency Medicine 2012 20(Suppl 2):P38.

- M. Kankaanpää et al. Comparison of the use of comprehensive point-of-care test panel to conventional laboratory process in emergency department. BMC Emerg Med 2018; 18, 43.

- Lee-Lewandrowski E, Nichols J, Van Cott E et al. Implementation of a Rapid Whole Blood D-Dimer Test in the Emergency Department of an Urban Academic Medical Center: Impact on ED Length of Stay and Ancillary Test Utilization. American Journal of Clinical Pathology 2009; 132, 3.

- Singer AJ et al. Early point-of-care testing at triage reduces care time in stable adult emergency department patients, J Emerg Med 2018; 55,2.

- Chaisirin W et al. Role of point-of-care testing in reducing time to treatment decision-making in urgency patients: A randomized controlled trial. West J Emerg Med 2020; 21, 2.

- Pines JM et al. Integrating point-of-care testing into a community emergency department: A mixed-methods evaluation. Acad Emerg Med 2018; 25, 10.

- M. Kankaanpää et al. Use of point-of-care testing and early assessment model reduces length of stay for ambulatory patients in an emergency department. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2016; 24, 1.

- St. John A, Price CP. Existing and emerging technologies for point-of-care testing. Clin Biochem Rev 2014; 35, 3.

- Singer AJ et al. Comprehensive bedside point of care testing in critical ED patients: a before and after study. Am J Emerg Med 2015; 33, 6.

May contain information that is not supported by performance and intended use claims of Radiometer's products. See also Legal info.

Acute care testing handbook

Get the acute care testing handbook

Your practical guide to critical parameters in acute care testing.

Download nowScientific webinars

Check out the list of webinars

Radiometer and acutecaretesting.org present free educational webinars on topics surrounding acute care testing presented by international experts.

Go to webinars